Although I have sometimes been called upon to treat ancient manuscripts on parchment and papyrus, the earliest works on paper that I had conserved were Italian Old Master drawings and German engravings from the early 15th century. That is until now, after I was asked by curator, Antonia Lovelace, from Leeds Museums and Galleries to conserve and mount two sheets from a Qur’an for the new Visions of Asia gallery at Leeds City Museum.

The sheets have been attributed by Tim Stanley, from the V&A, to Iran (or more broadly, ‘Eastern Islamic lands’) and dated to the 13th century. These papers, at more than 700 years old, pre-date the introduction of papermaking to England, in about 1495, by some 200-300 years. What is even more remarkable is the good condition and strength of the papers and the vividness of the ink and colours. Although Western papermaking probably owes its origins to Muslims living in Spain in the 10th century, Arab techniques of papermaking differ in several respects.

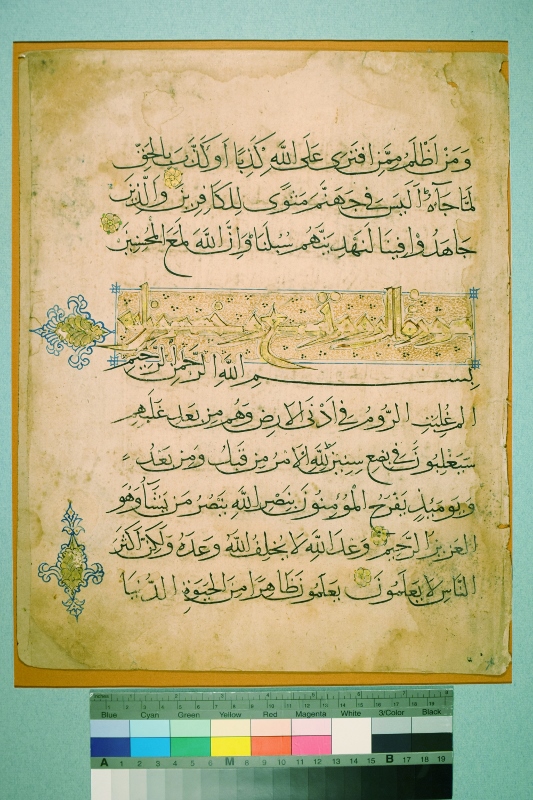

One of the Qur’an sheets before removing from its old mount

The early Western papers that I usually encounter are made from recycled rags such as linen, hemp and cotton. Early Arab papermakers used plant material, such as flax, to make their papers. Hand-made, Western paper was often sized with gelatine and pressed between woollen felts to impart surface texture, but Arabic papers were coated with starch and afterwards burnished with smooth stones or other such tools to give a highly polished surface on both sides.

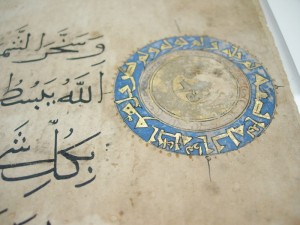

Light reflecting off the burnished surface of the Qur’an paper

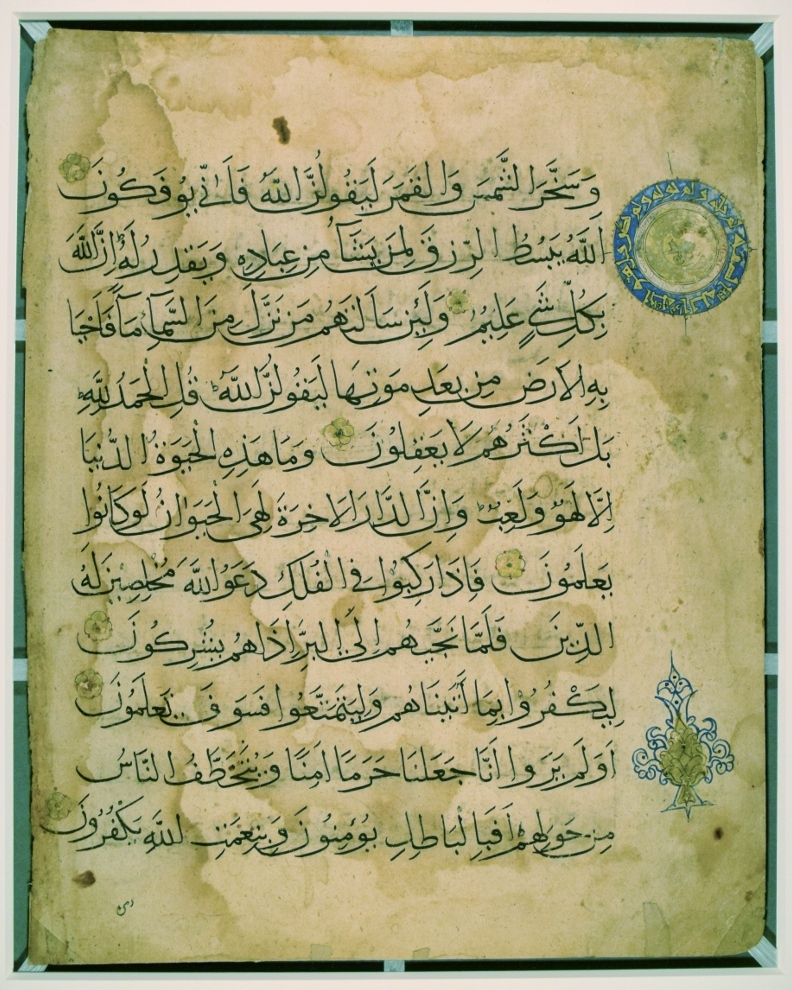

The Leeds Qur’an sheets are written by a calligrapher, probably using a reed pen, in black ink. Elements of the design are decorated with gold leaf, lapis lazuli (ultramarine) and touches of green and red paint bound in gum Arabic.

Details of the gold leaf, black ink and pigments used to illuminate the Qur’an

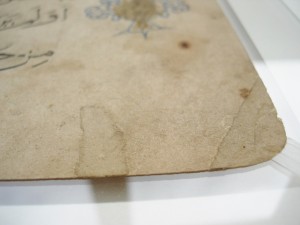

The conservation treatment required lifting the sheets from old, unsuitable mounts. These mounts had hidden the back of the sheets, where the text continues, so it was exciting to reveal these to Antonia. At some point in their history they have suffered from some water damage although it was decided not to try to remove these due to the risk to the paper and the ink in doing so. Further treatment was fairly minimal including removing some modern hinging tapes, unfolding creased edges and repairing small tears. There are already some old repairs to the pages which could easily be over 100 years old and these were left in place.

Detail of old repairs which were left in situ

A requirement of the new mounts was that both sides of the Qur’an manuscript sheets could be displayed. Constructed from thick 100% cotton, acid-free mount board, an acrylic window in the back of the mount now allows the verso to be viewed as well. The sheets are secured to the mount with thin but strong strips of Japanese gampi paper. These are adhered to the sheets with wheat starch paste then attached to the acrylic and mount with Evacon-R EVA adhesive.

Detail of one of the Japanese, gampi paper hinges

The new, double-sided mount before attaching the Qur’an sheet

One of the Qur’an sheets in its new, double-sided mount (with grey card behind to show position of gampi hinges)

When framed, these two pages from the Holy Qur’an will be important exhibits in the new gallery display which is due to open in July. It is a rare chance in this country, outside of London, to see such early examples of Islamic calligraphy and illumination.